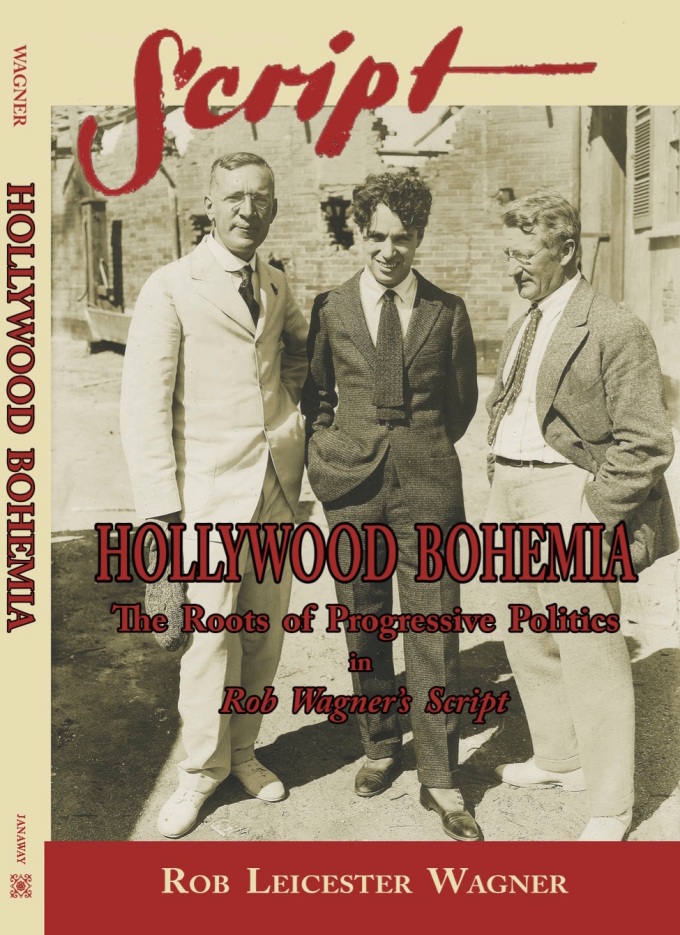

silent movies

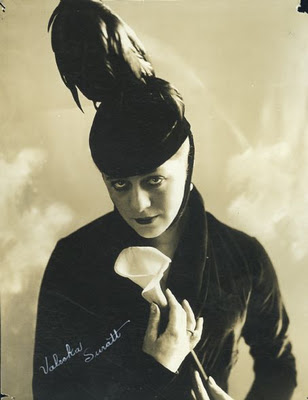

Valeska Suratt: Fashion Provocateur

By accident of birth, Valeska Suratt missed her calling as the leading femme fatale of the silent screen. That honor went to Theda Bara. By the time Valeska made her screen debut in “The Immigrant” in 1915, she was already 32 years old and her youthful glow was fading.

Suratt made only a handful of films as a second-tier vamp in the shadow of Bara, but if she minded she never let it show. She had a full-throttle career in vaudeville and on Broadway in the first two decades of the 20th century and wore her reputation as a clotheshorse with pride. Suratt may have astonished movie audiences as she had onscreen men for breakfast, but she was better known for tearing to shreds the constrictions women faced in the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

Although her given name rings exotic, Valeska Suratt (originally spelled Surratt) was a Midwestern girl to the bone. In separate passport applications, Valeska claimed she was born on June 28, 1883, or 1884, in Owensville, Indiana. Her father, Ralph Suratt, was a native of West Virginia and her mother, Anna Mathews, was born and raised in Owensville.

Ralph and Anna married in 1878, and Valeska was the second of four children. Her brother, Austin, was born in 1879, followed by Valeska, and then Leah in 1884. The baby of the family, Richard, arrived in 1890. The siblings also had a half-sister, Myrtle, from Anna’s first marriage to Dr. James Strickland. Myrtle was 11 years older than Valeska. When Valeska was 5, the family moved to Terre Haute.

Valeska was a bundle of contractions. A member of the Bahá’í Faith, she was deeply religious and a devoted student of the Bible. She possessed a keen business sense and was adventurous. But she was also eccentric and unpredictable, which often undermined her business acumen. At a time when it was scandalous for a small town girl to become stage actress, Valeska was a pillar of the community in Terre Haute. She looked after her parents and siblings and she donated $500 a week to the Red Cross during World War I.

She was tall compared to most women of the era, standing 5 feet, 8 inches in her stocking feet. She had chestnut brown hair, gray-blue eyes, full lips, a broad forehead and an oval face. She was mistaken for a Gibson Girl, but she wasn’t. She did, though, play one on stage.

The Suratt family was lower middle class, and despite two years of voice and singing lessons in Chicago her speech and mannerisms remained rough around the edges. Yet it was perhaps the only major criticism of her stage performances. Her throaty singing voice, high-priced New York and Parisian costume designs and her act as a sexual provocateur made her wildly popular.

An indifferent student, she quit school at 16 to work for Clare Sisters Photography Studio retouching photographs. Her work on photos of elegantly dressed women inspired her to pursue a fashion career. She took a job as an assistant to a milliner at a department store in Indianapolis where she learned design and apprenticed as a seamstress. She also worked as a wholesale buyer for the W.H. Block Department Store.

While developing her fashion design skills, she first appeared on the stage in Chicago, and by 1900 was working in vaudeville and touring South America and England with Billy Gould, whom she would marry in 1904. But her career had stalled. She was not getting roles that displayed her fashion sense with a figure to pull it off.

In 1906, she designed an elegant tight-fitting blackless black dress. In a move that has since become a Hollywood cliché, she chose a high-end New York hotel frequented by theatrical producers and made a grand entrance down the staircase to the hotel lobby to attract attention. It worked. Producer Edward Edleston spied her and made her his lead in “The Belle of Mayfair.”

Suratt made her Broadway debut in “Mayfair” on Dec. 3, 1906, and her show-stopping song “Why Do They Call Me a Gibson Girl?” became her signature tune. She followed with “Hip! Hip! Hooray!” in 1907.

On April 25, 1910, she appeared in “The Girl with the Whooping Cough” that promised to scandalize the East Coast with Suratt’s “corsetless New York debut” at the New York Theater.

A critic for the New York Sun was unimpressed, but gave Suratt credit for sort of saving the day: “Dramatic art had a boost last night through the modest effort to entertain offered by Valeska Suratt in corsetless gowns. Miss Suratt had long promised the waiting world that on this occasion she would positively appear without corsets. Whether she did or not does not matter much. The effect on dramatic art was the same … “Without Miss Suratt the piece would have been unutterably dull and stupid. With her it wasn’t refined. There wasn’t anything in it that hadn’t been served up in similar farces for the past three generations. The lines that made the most frantic effort to be suggestive fell flat, even with an audience, which was hungry and thirsty for that particular kind of nourishment. The members of the cast, particularly the women, were coarse and strident, and needed stage managing.”

However, New York Mayor William Jay Gaynor enhanced Suratt’s reputation for pushing sexual boundaries when he determined “Whooping Cough” was “salacious” and shut down the production.

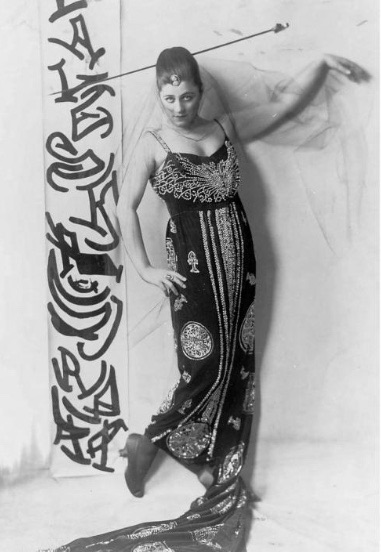

Whatever vulgarities in her performances were trivial compared to her sex appeal and fashion sense. Suratt was perhaps the first performer in modern theater to establish fashion fetishism that prompted magazines like “Vogue” to obsess over every minute detail of her elaborate wardrobe that required multiple changes during a single performance. Earning as much as $3,000 a week, she had full control over production, stage design, costumes and the writers. Audiences lapped up these over-the-top displays although Suratt would have been better served if she employed a disciplined wardrobe supervisor.

In their book, “Musical Comedy in America,” Cecil A. Smith and Glenn Litton noted that the play “The Red Rose” (1911) “was a window display for the overdressed Valeska Suratt, who designed her own innumerable costumes, the most overpowering of which were a Spanish affair in canary yellow and black … and a flaming harem skirt with the effect of a ‘perpendicular rainbow.’ ”

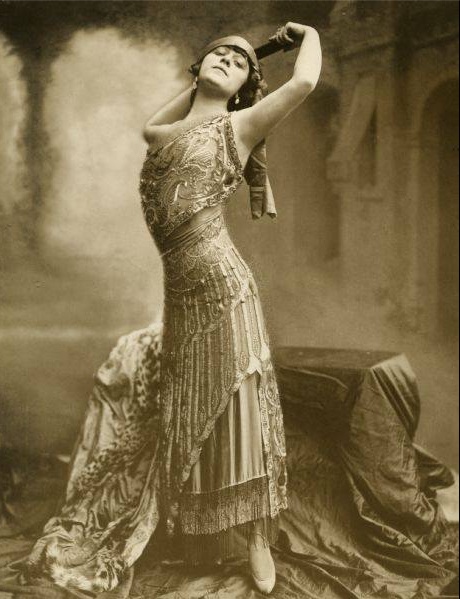

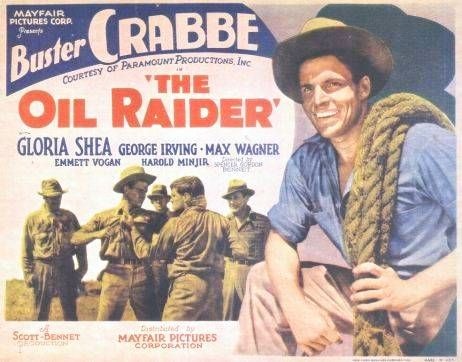

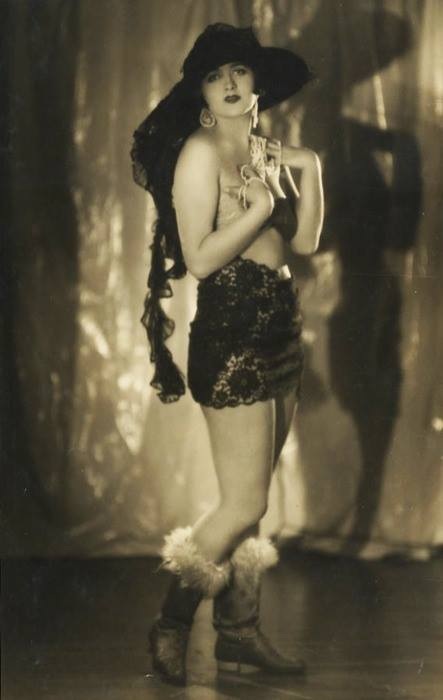

Many of Suratt’s costumes were reportedly valued at $20,000 apiece. (Photo courtesy Joseph Hall/ Shields Collection ex-Culver Service)

By late 1910, Suratt was appearing in 30-minute mini-revues. One such playlet was the “Bouffe Variety” at Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater. She co-starred with Fletcher Norton, who she would also marry. With “Bouffe Variety,” Anthony Slide described Suratt in “The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville” as “a sultry and exotic leading lady of generally tawdry melodramas.”

These productions led to her femme fatale persona – usually young women of modest means or from the slums who yearn for the finer things in life – that eventually garnered Suratt leading parts in William Fox’s films. These roles were not a stretch for Suratt given her own modest background. She couldn’t pull off the sophisticated seductress because her Midwestern lower middle-class roots usually gave her away. One critic noted that every time she opened her mouth to sing a lusty song, out came a Chicago accent. Not that she cared much.

Critics might have described her acts as “coarse” and “vulgar,” but Suratt, fully aware of her limitations, was marketing a brand that commanded full houses. For Green Book Magazine, she wrote in 1915 that, “It’s my personality that wins for me. I’m no singer. Heaps of people can beat me dancing. Precious few of them, though, get the salary I do. Why? Because I’m me!”

Suratt’s individuality was paramount to her success. She and she alone commanded the stage and loathed to share it with anyone else. A review of her stage production photos and studio portraits reveal her singularity: Full length portraits displaying her hourglass figure, elaborate costumes and a handsome face. Photographs of Suratt with leading men were rare and Suratt sharing space with another woman were almost non-existent.

And therein lies the core of Suratt’s initial success and her ultimate failure in films: Her demands for complete control of her image and her reluctance to compromise inevitably led to conflicts while working in films.

She only appeared in 11 movies, mostly as vamps and femmes fatales, between 1915 and 1917. William Fox had purchased the film rights to “A Fool There Was” about a young diplomat seduced and ruined by a woman only known as “The Vampire.” Fox considered and rejected Suratt for the part and then chose Theda Bara. The role launched Bara into superstardom as a “vamp” and relegated Suratt to similar parts in lesser films. Fox, though, thought enough of Suratt’s business sense to send her to France, England and Monte Carlo in March 1916 to act as his representative in future projects.

For a performer like Suratt, filmmaking at best was a collaborative effort and at worst a vision held solely by the director. The medium forced her to relinquish control of the script, choice of costumes and how she presented herself on the screen.

Time and changing tastes among moviegoers also robbed her of a sustaining film career. The Gibson Girl was no longer fashionable in modern America. By 1915, the popularity of Suratt’s hourglass figure, which was beginning to fill out after she hit 30, gave way to the slimmer, more boyish bodies of performers Lillian Lorraine and Irene Castle. Suratt played vamps with great success in “She,” “The Slave” and “Siren” in 1917, but the more alluring and youthful-looking Theda Bara, although only two years younger than Suratt, stubbornly held the vamp mantle. Yet, even by 1917, moviegoers were already bored with vamp characters and moved on.

Another reason for Suratt’s failure in films that can’t be ignored was her erratic behavior throughout most of her young adult life that may have evolved into mental illness as she got older. Suratt was very well a diva with an artistic temperament that probably made working with her difficult. But there were signs before she was 30 years old that she was unstable. By January 1911, Suratt had divorced Billy Gould and was engaged to Robert T. Mackay, a real estate manager deeply in love with the actress.

On Jan. 14, Mackay watched his fiancée’s Saturday matinee at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York and then stayed for a rehearsal. Suratt asked Mackay to fetch her some sandwiches. He demurred, complaining he wasn’t a servant, but she sweet-talked him into getting the food.

While Mackay was on his errand, Suratt left the theater with co-star Fletcher Norton in a limousine and drove to the New Jersey shore where a justice of the peace married the couple in a brief ceremony. Meanwhile, Mackay arrived at theater with sandwiches in hand only to find his girl missing. Suratt’s maid took pity on him and said his fiancée had married Norton. Mackay collapsed in a heap and cried. Moments later Suratt arrived with her new husband, observed Mackay’s anguish, and fell to the floor with a theatrical flourish at Mackay’s side to weep uncontrollably with him.

In December 1911, Norton, citing infidelity, filed for divorce. Suratt’s maid testified at the trial that Suratt told her that she married Norton in a “fit of pique” because Mackay had annoyed her. Mackay later became Suratt’s lover. When Suratt filed for bankruptcy on June 29, 1912, Mackay was her biggest creditor at $14,750.

Suratt’s stage career sputtered in the 1920s. She peaked as the headliner in “The Dynamic Force of Vaudeville” in 1920 and appeared in the Broadway production of the “Spice of 1922” during that summer. Her last performance was in “The Frolics of 1929.”

Recognizing that there was not a much of a demand for 46-year-old sexual provocateurs, Suratt contemplated retirement in the late 1920s, but she wanted at least another shot at a film career. She commissioned author Mírzá Aḥmad Sohráb, leader of the Reform Bahá’í Movement in the United States, to co-write a script on the life of Mary Magdalene. The film would serve as a vehicle for Suratt’s comeback. Sohráb completed the script and Suratt showed it to Cecil B. DeMille. The director kept the scenario for some months and then returned it without comment.

When DeMille’s “The King of Kings” hit movie theaters in 1927, Suratt believed the film was based on Sohráb’s script. She sued DeMille alleging plagiarism.

Before the lawsuit went to trial, Suratt met her friend, Julia Chanler, a fellow Bahá’í and co-founder of the New History Society, in New York. Suratt had hoped Chanler’s introduction to New York Governor Alfred E. Smith would help further her cause against DeMille. Smith was powerless to do anything other than give Suratt a letter of recommendation, which Suratt thought was important. During the New York visit, a stage version of “The Kings of Kings” was playing on Broadway. Suratt and Chanler decided to attend a performance.

It was immediately clear to Chanler the production was based on the Gospels taken directly from the Bible, but Suratt saw the story as a blatant rip-off from the Sohráb script. Chanler and Suratt agreed to disagree on the origins of the script.nThe lawsuit went to trial in 1930 and it was eventually settled out of court.

Students of silent cinema claim that DeMille probably blacklisted Suratt in Hollywood, preventing her from acting in films. This is highly unlikely. By 1930, Suratt had been absent from movies for 13 years. Her glory days in vaudeville and on Broadway had long since past, and she was approaching 50, which severely limited her appeal in the kind of roles she was accustomed to having. DeMille hardly needed to go through the trouble of keeping Suratt off studio lots.

Yet the Mary Magdalene script was indicative of her obsession with the Bible and the life of Virgin Mary. Later in her life, Suratt attempted to interest publishers to produce her autobiography. She also approached the Hearst newspaper chain, which sent a reporter to read her manuscript. The reporter discovered the autobiography was about the Virgin Mary and Suratt believed she was Mary. “She was completely batty,” the reporter later said.

No one knows, aside perhaps surviving members of the Suratt family, whether Valeska suffered from mental illness and whether she really thought of herself as the mother of God. It’s entirely possible she wrote of the Virgin Mary as an “autobiography,” which is not an uncommon writing technique. What is known is that she immersed herself in the study of the Bible and wrote frequently about her religious beliefs.

Suratt died in nursing home in Washington, D.C. on July 2, 1962, and buried in her beloved hometown of Terre Haute at the Highland Lawn Cemetery.

Today, Suratt is credited for popularizing the Gibson Girl with a sexual edge and had helped loosen the boundaries of acceptable mass entertainment offered by female performers. On film, she remains one of four original silent screen vamps with Theda Bara, Louise Glaum and Virginia Pearson.

Valeska Suratt Internet Movie Database Filmography

SOURCES:

New York Times, Dec. 10, 1911

New York Dramatic Mirror, November 1914

Motion Picture World, Nov. 21, 1914

Valeska Suratt passport application, Feb. 2, 1916

Motography, Vol XVII, No. 10, 1917

Motion Picture World, July 21, 1917

Valeska Suratt passport application, June 27, 1919

Motion Picture World, Sept. 17, 1927

Indianapolis Tribune-Star, Nov. 19, 2006

Indianapolis Tribune-Star, July, 3, 2011

Valeska Suratt, ancestry.com (accessed Oct. 3, 2014)

Broadway Photographs website, The Visual Culture of American Theater 1865-1965 by David S. Shields (accessed Oct. 9, 2014)

Sarrett/Sarratt/Surratt Families of America (SFA), freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com (accessed Oct. 10, 2014)

“The Revolution in Christian Morals”: Lambeth 1930-Resolution #15 History & Perspective” by Theresa Notare (Catholic University of America), 1930

“From Gaslight to Dawn,” an autobiography by Julie Chanler (The New History Foundation), 1956

“Musical Comedy in America” by Cecil A. Smith and Glenn Litton (Routledge), 1987

“The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville” by Anthony Slide (Greenwood), 1994

“Vamp: The Rise and Fall of Theda Bara” by Eve Golden (Vestal Press) 1998

“Blue Vaudeville: Sex, Morals and the Mass Marketing of Amusement, 1895-1915” by Andrew L. Erdman (McFarland & Co.), 2007

“Theda Bara: A Biography of Silent Screen Vamp, with a Filmography” by Ronald Genini (McFarland & Co., reprint edition), 2012

Natalie Kingston: When Talent Wasn’t Enough

Talent doesn’t necessarily translate to success in Hollywood. Stage experience, singing and dancing – all prerequisites for a shot at film stardom during the silent and early talkie era – often couldn’t compete against luck and timing. For every Joan Crawford and Myrna Loy who had careers that began as dancers and found success on the screen, there were the Natalie Kingstons and Sally Rands with film careers that started, stopped and then just wilted against the competition of fresher faces.

Natalie Kingston, born Natalia Ringstrom of a noble Spanish legacy, had a solid foundation in show business that should have given her an edge against the wannabe actors who came to Hollywood without experience.

Kingston appeared in about 60 films as a Mack Sennett girl and WAMPAS star, but her comedy short films more or less determined her career arc. For every move into dramatic acting, she found herself in another comedy short – a “Hotel California” loop where she could check out anytime but she couldn’t ever leave.

Born in Vallejo, Calif., on May 19, 1905, Kingston was the daughter of Sigurd Adolph Ringstrom, a Swede, and Natalia “Tala” Vallejo Haraszthy, a member of the Haraszthy winemaking dynasty in the Sonoma Valley. Natalie’s maternal grandfather was the Hungarian Attila Haraszthy and her grandmother was Natalia Veneranda Vallejo.

Natalie’s maternal great-grandfather, General Mariano Vallejo, had commanded the Mexican Army in California and her great-grandfather, Agoston Haraszthy, transformed the Sonoma Valley into wine country with a global reach.

Winemaking, however, didn’t interest Natalie, but another family endeavor did. Her great-uncle, Arpad Haraszthy, was co-founder of the Bohemian Club, which put on the legendary Bohemian Grove Plays. Her cousin, Natalia Vallejo Haraszthy, who was five months older than Natalie and shared the same name as Natalie’s mother, was an actress, ballerina and dancer. She appeared on stage at Carnegie Hall, the Palace Theater in New York and was a regular performer on the Keith-Orpheum circuit on the West Coast. Following her retirement from the stage, she taught dance in Van Nuys. Natalie’s younger sister, Eleanor (also spelled Elinor), also took the stage name Kingston and was a dancer working as a $40-a-week extra and chorus girl in musicals.

Natalia Vallejo Haraszthy, Natalie Kingston’s cousin, was a dancer in her own right. (Photo Courtesy UC Berkeley/Bancroft Collection)

For Natalie, dancing was a natural choice, although she took a circuitous route to show business. She was educated at the Dominican Catholic convent in San Rafael, and then spent her final year at a public high school. She reportedly studied law briefly in the Bay Area before she trained as a dancer in small clubs and restaurants. Among her routines was La Jota, the Spanish folk dance of Aragon. She was well suited as a dancer. She was leggy and taller than most chorus girls at 5 feet, 6 inches, and weighing a trim 125 pounds. She had hazel eyes, an olive complexion and her dark brown hair parted down the middle accented her Spanish beauty.

Taking the stage name “Kingston,” Natalie was only 15 years old when she won a spot as a dancer in the Broadway Brevities 1920 revue at the Winter Gardens Theater in New York (begging the question of whether she lied about her age to get the job) with Eddie Cantor headlining the cast.

An original two-act musical revue, the show debuted on Sept. 29, 1920, and ran through Dec. 18 for 105 performances. In the meantime, Kingston’s appearance on Broadway required her to perform publicity campaigns to promote the show and herself as a budding star. Midway through the run, organizers at the North River Apple Auction, celebrating National Apple Week, crowned Kingston the “Queen of Apples,” making her a spokeswoman for the industry to tout the health benefits of the fruit.

Once Broadway Brevities 1920 ended, Kingston found no new offers in New York. She returned to San Francisco, but quickly discovered her Broadway experience opened doors for her on the West Coast no matter how brief her tenure on the New York stage.

Less than a month after her return, Jack Holland, a popular Bay Area performer, snatched her up for his own dance revue at the Coronado Hotel in San Francisco. Holland and Kingston then alternated throughout 1921 between Tait’s Café and Harry Marquard’s Café, both highly popular nightclubs specializing in presenting dance cabarets. Holland also paired Kingston with other lead dancers, including Lavinia Winn, and backed the principals with six chorus girls.

Holland and Kingston kept a grueling two-year schedule, which helped Kingston hone her acrobatic skills. Under Holland’s tutelage, Kingston developed the discipline to take her talent on the road. At 16 years old, she was a veteran hoofer.

In 1923, she attracted the attention of the brother-sister Fanchon “Fannie” and Marco Wolff vaudeville team. The siblings founded Fanchon and Marco in 1919 that started with music and dance numbers. The act evolved by 1921 into the “Sunkist Beauties” dance troupe, a West Coast version of The Rockettes.

Fanchon and Marco were more responsible with the teenage dancer than her Broadway employers, ensuring Kingston was 18 years old and properly chaperoned while on the road.

When Kingston joined troupe, Fanchon and Marco had just developed elaborately themed live stage shows, called “The Ideas.” Fifty-two individually themed Idea productions were staged through 1930 that included dancing, singing and vaudeville acts. The shows were about 15 minutes long, ran three to four weeks, and served as prologues to feature films. Natalie joined the dance troupe now dubbed the Fanchonettes.

Natalie, far right front row, in a Fanchon and Marco production. (Photo Courtesy Huntington Library)

The Fanchonettes were the major draw, according to the Bismarck Tribune. The newspaper noted on May 27, 1920, that the troupe had the “world’s most beautiful women garbed in radiant smiles – and not much more.”

Fanchon and Marco divided the Fanchonettes into five separate groups to perform in Vancouver, B.C., Seattle, Portland, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Kingston performed the northernmost tours. In a “Carnival” themed production at the Strand Theater in Vancouver during the summer of 1923, Kingston performed the Indian Dance, while she paired with dancer David Murray in the “Cabaret Queens” production also at the Strand.

Other performers during this period included Joan Crawford, Mae West and Janet Gaynor, although whether they shared the stage with Kingston is unknown. Myrna Loy joined the troupe in 1924 after Kingston had left for a film career.

Under the Fanchon and Marco banner, Kingston was a featured dancer or always a front-line chorus performer. In the fall of 1923, Mack Sennett was in the audience of a Fanchon and Marco revue and caught Kingston’s dance act. He persuaded her to join his studio to appear in his two-reel comedies.

Kingston likely saw the offer as an entré as a serious actress and agreed to appear in a minor role for “The Dare-Devil” featuring Ben Turpin and Harry Gribbon. Sennett released the film on Nov. 25, 1923.

But Kingston didn’t immediately give up her Fanchon and Marco gig. She continued her Idea prologue performances. She appeared, for example, on Jan. 23, 1924, at Loew’s Theater in Los Angeles for the troupe’s “A Night at the Harem” revue backed by a 15-member orchestra and 14 chorus girls. She performed the Peacock Dance with her now standard acrobatic flourishes.

Natalie Kingston at the height of her fame as a dancer. (Photo Courtesy Edward Bower Hesser Collection)

Her Loew’s performance was likely one of her last for Fanchon and Marco. She signed a contract with Sennett and was already filming a minor role in “The Half-Back of Notre Dame” (1924) with Harry Gribbon, followed by “The Hollywood Kid” (1924) with Charles Murray.

Her early films consisted of set decoration as a “bathing girl” or someone’s pretty daughter. Film schedules were always tight while working on two-reelers. Kingston’s roles likely took only a couple of days to shoot, a sharp contrast to the hectic pace of dance revues up and down the West Coast. Even dancing parts in an occasional Cecil B. DeMille film couldn’t have occupied all of her time.

She spent a year and a half with Sennett before terminating her contract in an effort to get larger roles in dramatic pictures. Yet she often returned to Sennett as a free-lancer.

She signed contracts with FBO, Paramount, Fox and Universal to increase her exposure as a serious actress. For Paramount Pictures in 1926, she made three comedies: “Miss Brewster’s Millions,” “The Cat’s Pajamas” and “Wet Paint.” She had a small role in the World War I melodrama “Framed” (1927), but did a nice turn earning third billing in Fox’s “Street Angel” (1928), which featured Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell. The role led to two Tarzan pictures, “Tarzan the Mighty” (1928) and “Tarzan the Tiger” (1929) where she shared the lead with Frank Merrill.

Her films after the Tarzan series marked a decline in offers for dramatic parts. She played a gangster’s moll in “The Last of the Duanes” (1930), but that same year she found herself back on the Sennett lot in an uncredited “girlfriend” part in “The Chumps” (1930).

Unlike many of her colleagues, such as Sally Rand who spoke with a lisp, Kingston did not struggle with sound in the late 1920s. She had a strong screen presence and a voice to match. She continued free-lancing by working for Sennett on comedies and the occasional dramatic role for Universal. Yet she never gained enough traction to propel her career as a dramatic actress in the 1930s.

The Hollywood trade publications often published items touting her dancing skills and the Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers named her WAMPAS Star of 1927 to give her a career boost. But many WAMPAS stars saw their careers fizzle in the aftermath of the publicity.

As a WAMPAS star, Natalie was required to pose for publicity photos in race cars she likely would have no interest in driving, including this 1927 Jackman Special.

Kingston and fellow 1927 WAMPAS stars Martha Sleeper and Barbara Kent managed steady employment in the 1920s only to see roles dry up by the mid-1930s. Other 1927 WAMPAS alumni – Sally Phipps, Patricia Avery, Mary McAllister, Gladys McConnell and Sally Rand – could never manage to get their careers off the ground. With the exception of Rand, who was hugely popular as a fan dancer, the others fell into obscurity.

Perhaps recognizing as early as 1928 that acting was not in her future, Kingston took real estate law classes to better manage her property holdings. The same year she married George Andersch, a real estate broker, banker, and later a mining engineer with extensive mining leases in the Mojave Desert.

Following an uncredited part in Universal’s “Only Yesterday,” which was released on Nov. 1, 1933, Kingston retired from films. She never returned to moviemaking, preferring to live quietly with her husband in West Hills, a Los Angeles suburb. She died on Feb. 2, 1991.

Natalie Kingston Internet Movie Database Biography

SOURCES:

San Francisco Call, July 31, 1913

Bismarck Tribune, May 27, 1920

New York Tribune, Sept. 26, 1920

Washington Herald, Nov. 5, 1920

Variety, Jan. 21, 1921

Variety, May 13, 1921

Variety, July 29, 1921

Variety, Dec. 6, 1921

San Francisco Chronicle, July 14, 1923

San Francisco Chronicle, July 20, 1923

San Francisco Chronicle, July 30, 1923

Variety, Jan. 24, 1924

Picture-Play Magazine, March 1925

San Francisco News Letter, Aug. 8, 1925

Variety, December 1925

Variety, June 23, 1926

Motion Picture News, July 27, 1926

The Kingsport (Tenn.) Times, Jan 9, 1927

Motion Picture News, Jan. 27, 1927

Motion Picture News, June 10, 1927

Motion Picture Classic, November 1928

Hollywood Filmograph, July 26, 1930

Motion Picture News, July 27, 1930

Variety, Nov. 29, 1932

Monterey Peninsula Herald, Nov. 3, 1989

“California Journal of Mines and Geology, Quarterly Chapter of State Mineralogist Report, XXXVI”

“Strong Wine: The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy” by Brian McGinty (Stanford University Press), 1998

“History of San Fernando Valley” by Frank McCleunan Keffer (Stillman Print Co.), 1934

Natalie Ringstrom, ancestry.com (accessed Oct. 1, 2014)

RootsWeb’s World Connect Project (accessed Oct. 1, 2014)

FanhconandMarco.com (accessed Oct. 2, 2014)

StreetSwing.com (accessed, Oct. 2, 2014)

The Short and Frenetic Life of Harry Sweet

Harry Sweet, the comedic actor, director and early innovator of the “slow burn” comedy routines that made performers like Edgar Kennedy eagerly sought for film shorts, had a career that could have achieved greatness if he hadn’t died tragically in a plane crash at the age of 32.

He rarely paused for a moment’s rest, appearing in front or behind the camera in more than 150 films over a 14-year period. He was a man on a mission to learn his craft, and the studios he worked for rewarded him with more assignments and more responsibilities. It was a frenetic pace made especially arduous given that many of his co-stars in his early films were animals not known for their cooperative nature.

Today, as much as 95 percent of Sweet’s films have been lost, denying cinema scholars the ability to accurately assess his body of work. But during his time, there was little doubt among his contemporaries that given half the chance and a healthy film budget, he may have rivaled some of the greats of the silent era.

Harry Sweet was born Harry Swett on Oct. 2, 1901. His father, Don Alvo Swett, was a New Englander, and his mother, Jane Alexander, had emigrated from Ireland to the United States. The family lived in Teller County, Colorado, where his father was a postal worker. Sweet had one sister, Glencora, who was eight years younger.

The Swett family moved to Reno, Nevada, in 1912, and Jane Swett died there in 1915 at the age of 50. Although Harry’s father would later move to Los Angeles, the three remained in Reno at least until 1918 where Harry and his sister attended local schools

While in high school, Harry worked in local movie houses and gained experience as a motion picture projectionist. By the time he left school, he was also a skilled acrobatic performer. Whether he belonged to an acrobatic company is unknown. But following his high school graduation, he traveled to Hollywood and immediately found a job at L-KO Kompany, a small film studio lot under the umbrella of Universal Studios that had been specializing in one- and two-reeler short comedies since 1914.

Keystone Kops veteran director Henry “Pathé” Lehrman founded L-KO after a falling out with Ford Sterling after Lehrman and Sterling formed Sterling Comedies at Universal. Instead of leaving Universal, Lehrman formed L-KO. It was never a top tier comedy studio to match Mack Sennett or Hal Roach, but it did produce a steady stream of quality films, including several shorts from Charley Chase.

Sweet arrived in Hollywood in 1919 when the Spanish influenza epidemic was still raging through California. It hit the actors and film crews hard at L-KO lot and Universal shut it down as a precautionary measure. Sweet managed to appear in L-KO’s last film, “The Oriental Romeo” featuring Chai Hong and directed by Jess Robins.

Sweet moved seamlessly over to Century Films, which produced the Baby Peggy and Brownie the Wonder Dog comedy two-reelers along with other animal shorts that included the “Century Lions” and the “Century Dogs.” Sweet would polish his acting chops on the Century Lions and Brownie films under the direction of Fred Hibbard and Tom Buckingham.

While Sweet regularly appeared opposite the Century animals, the studio was also eager to promote Sweet on his own merits. In 1921, Sweet signed a two-year contract with Century to star in a series of shorts. The studio announced in June that 18 new two-reelers would feature Sweet in lead roles to complement 18 Brownie shorts. Century rounded out the schedule with 16 comedies for Charles Dorety, who also spent considerable screen time opposite the Century animals.

Harry Sweet with Brownie the Wonder Dog and actress Louise Lorraine while working for Century Films. (Photo originally appeared in The Film Daily.)

Sweet was immensely popular on the set. Gloria Morgan, who would become Sweet’s script supervisor when he was with RKO toward the end of his life, described him as “a very gentle, funny man with a delicious sense of humor.” Directors wanted him for his acrobatic skills and his insistence that he work without a stunt double. He was often cast as a rube living in rural America. He allowed his routines to slowly build to a huge climax that required physical agility in often dangerous and elaborate finales. Through the 1920s, he gained weight, although it didn’t hinder his ability to construct comedy routines demanding stunt gags.

In the spring of 1924, Sweet jumped from Century to Mack Sennett. Richard Jones, the supervising director for Sennett, may have had Sweet in mind to direct rather than star in films on the Sennett lot. Whether that was a promise Jones made to Sweet before he joined Sennett or came about later is unclear. However, almost immediately Jones suggested that Sweet could direct Sennett comedy stars better than directors who didn’t have the acting experience in front of the camera.

Sweet’s only previous directing experience was “What! No Spinach?” for the Standard Photoplay Company in 1920. Yet Jones was confident of the actor’s ability and gave him the Ben Turpin vehicle “Romeo and Juliet” (1924) and “The First 100 Years” with Harry Langdon and Alice Day. Both films proved to be hits.

The Sennett lot gave Sweet the latitude to perfect his comedic timing and helped him gain experience in dealing with a wide range of actors from Langdon to Natalie Kingston and Madeline Hurlock.

But since Sennett comedies adhered to a formula, Sweet wanted to experiment with the use of camera angles and editing to provide a fresh perspective to his films.

In March 1928, he produced “Rhythms of a Great City in Minor.” The film had a budget of only $164 ($2,281 in 2014 dollars) and was limited to less than one reel at about 850 feet. Sweet rounded up his actor and production crew friends that included Arthur Houseman, Charles Puffy, Lydia Yeamans Titus, Leslie Fenton, Betty Davis and Max Wagner. Davis was an occasional actor and film editor and likely helped Sweet edit the footage. Sweet also made an appearance in the film.

The short is an early example of guerrilla filmmaking, shooting footage without city permits on busy streets, atop transit buses and in alleyways. It also made extensive use of jump cuts. The film contained four stories, with a series of short jump cuts and tilted angles leading into the first story.

Sweet showed the film privately to impresario Sid Grauman, founder of the Egyptian and Chinese theaters. Grauman was sufficiently impressed to give his own private screening to Charlie Chaplin. The film never played outside Los Angeles and no copies are known to have survived. But it serves as an early example of Sweet’s determination to break outside the confines of conventional two-reel comedies.

Unlike many silent film actors and directors, Sweet successfully made the transition to talkies. A significant career move occurred in 1930 when he was tapped to run RKO’s short subject department. At the time FBO, Pathé and Radio Pictures were merging together to become RKO.

Harry Sweet, second from left, in the Century comedy Horse Sense with actress Alberta Vaughn, center. (Photo originally appeared in The Film Daily.)

Sweet’s first project was to transform Edgar Kennedy from playing second fiddle to Charley Chase and other big comedy stars of the day to a headliner. Kennedy was the master of the “slow burn” routine as the indignities would pile up and an exasperated Kennedy would attempt to hold his temper until he exploded. Sweet helped Kennedy develop the routine and exploit it in Kennedy’s “Mr. Average Man” series.

RKO released the first “Mr. Average Man” film, “Lemon Meringue,” on Aug. 3, 1931, that also featured Dot Farley, who would remain in the cast as “mother” through 1948. Sweet also directed a pair of “Whoopie Comedies” with Kennedy and Florence Lake. “Rough House Rhythm” was released in April 1931 and “All Gummed Up” followed a month later.

Sweet signed a new contract with RKO in March 1933 for another year as short subject director and to star in comedies.

On the afternoon of June 18, 1933, Sweet took screenwriter Howard “Hal” Davitt and Vera Williams, a 20-year-old bit player acting under the name of Claudette Ford and an acquaintance of Sweet, in his private plane to scout filming locations near Big Bear Lake. Sweet was an experienced pilot, who had flown single-engine airplanes for most of his adult life. He often flew goodwill and charity runs. His last goodwill flight was a trip in 1932 from Los Angeles to his old hometown Reno, where he visited old friends.

The trio left Glendale Airfield and landed at Big Bear airport where Sweet had hoped to meet a friend. When the friend failed to show up Sweet decided to fly over the lake.

Shortly before dusk at about 7:15 p.m., Sweet was at the controls and flying about 40 feet above the water. The engine failed and the aircraft plunged into the lake in about 20 feet of water. The plane was submerged except for the tail with its identification number visible.

About 50 men volunteered to recover the bodies and aircraft while the Department of Commerce identified the plane and Sweet as its owner from the serial number.

As darkness fell, the recovery operation halted, and resumed in the morning of June 19. An inquest held the same day determined that Sweet was the pilot. The rescue team pulled the bodies from the wreckage and autopsies determined that Davitt and Williams died from fractured skulls and Sweet had drowned. All three were found wedged at the front of the cockpit.

Williams’ body was returned to her father, George Hallar, in Toledo, Ohio, and Pierce Brothers Mortuary in Los Angeles took possession of Sweet’s body. Davitt’s mother in Boone, Iowa, was also notified.

“Good Housewrecking” with Kennedy was Sweet’s last film, which was released two days before the director died. Producer Lou Brock took over the “Mr. Average Man” series and supervised it for many years.

The limited budgets, length and often-formulaic nature of comedy short subjects made such films the redheaded stepchild of the film industry, especially at the larger studios. Appreciation for the genre didn’t occur until television began broadcasting episodes beginning in the 1960s. Had more of Sweet’s work survived, and perhaps surviving to see the “Mr. Average Man” series through to its end in 1948, he may have earned the same comedic acclamation as Edgar Kennedy, Laurel and Hardy and other kings of comedy short films.

Harry Sweet Internet Movie Database Biography

SOURCES:

The Film Daily, April 13, 1921

The Film Daily, April 22, 1921

The Film Daily, May 12, 1921

Exhibitors Herald, Oct. 22, 1921

Exhibitors Trade Review, Jan. 7, 1922

Exhibitors Herald, June 25, 1921

Exhibitors Herald, Sept. 10, 1921

Exhibitors Trade Review, Oct. 8, 1921

Exhibitors Herald, Nov. 4, 1921

Variety, April 12, 1924

Motion Picture News, Jan 27, 1927

Picture-Play Magazine, June 1928

The Film Daily, May 17, 1932

Motion Picture Daily, May 17, 1932

San Bernardino Sun, June 19, 1933

Oakland Tribune, June 19 1933

Times Recorder (Zanesville, Ohio), June 20, 1933

The Film Daily, June 21, 1933

Nevada State Journal, June 21, 1933

Café Roxy (accessed Sept. 9 2014)

“The Great Movie Shorts” by Leonard Maltin (Crown), 1972

Harry Swett, Ancestry.com

Jimmie Fidler: Hollywood’s most hated man

Hollywood gossip columnists come and go and few leave an indelible imprint in cinema history. Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper are perhaps the exceptions, given their intense and well-publicized rivalry and their advantage of having the strong support of their Los Angeles-based newspaper employers.

It’s the nature of the beast. Gossip is of the moment; replaced the next day with something new. Examination of a columnist’s work yields little tangible information that lends itself to substantial scholarly work of the film industry.

Jimmie Fidler, a notorious gossip columnist and entertainment radio commentator, outlasted the giants – Parsons, Hopper and Walter Winchell – by three decades. He earned more money, reached a wider audience and played hardball that outstripped the reputations of Parsons and Hopper for ruthlessness. Yet today he is forgotten, and few of his generation working in the film industry lamented his passing in 1988 at the age of 89.

Simply, Fidler was not a nice man, at least in print and on the air. He was the town scold and had a tendency to break the unwritten rule of biting the hand that fed him. But he generated huge revenue for his print and broadcast employers, even if they had to hold their noses to count their money.

Born James Marion Fidler on Aug. 26, 1898, in Memphis, Tenn., to William, a grocery clerk, and Belle Fidler, Jimmie was an only child. By the time he was 12 years old, the family moved to Lincoln, Miss., which accounted for his Southern drawl heard on his broadcasts.

He enlisted in the U.S. Marines at the age of 20 on Sept. 26, 1918; less than two months shy of the Armistice, so his service was brief. He was honorably discharged at the rank of lieutenant on June 25, 1919, and found himself with $60 in his pocket in Hollywood with dreams of becoming an actor.

He found work as an extra, but he quickly realized that he had no future, which is somewhat of a mystery. He was handsome, tall and thin with light brown hair and a strong jaw. But few directors took notice. He returned to his parents’ home in Memphis briefly in 1920 and owned an oil and hoe company, but returned to Hollywood the same year.

Fidler often claimed that he was the first Hollywood gossip columnist when he began his career in 1920. But Parsons had been writing gossip since 1914 and there is no evidence that Fidler turned to gossiping until 1934.

He spent most those 14 years working from hand to mouth as a press agent. He set up an office at Sunset and Cahuenga boulevards and established a roster actors. During the silent era, press agents worked as free-lancers, picking up actors and actress accounts on a weekly basis. Salaries ranged from $10 a week from lower tier actors to $150 a week from marquee names, such as Wallace Reid and Joan Crawford.

Fidler’s first job came from Edmund Lowe, who offered him offered him $25 a week to be his press agent. Soon, he was working a regular gig writing publicity for Cecil B. DeMille at Famous Players-Lasky.

Later, he moved his offices to Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street and set up his operation like a newspaper newsroom. He installed Ann Paraneas, who had worked for New York City newspaperman O.O. McIntyre for many years, on the “city desk” and added four reporters and nine studio contacts to his payroll.

Actors and studio execs genuinely liked Fidler. They found him hardworking, fair and seem to deliver a real benefit to their careers.

In 1931, he married Dorothy Lee, a petite 5-foot tall, 97-pound actress, who was already a veteran vaudeville performer by the time she met Fidler at age 19. She was a regular in the Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey comedies, gaining attention for her singing and dancing in the new talkies.

The marriage, however, was brief. The couple split up after six months and divorced after eight. Dorothy rented Fidler’s Toluca Lake house from Fidler, who went into a tailspin as his publicity business suffered.

In 1934, Fidler took a job as a press agent for a Los Angeles radio station. The salary was terrible and the job was well below Hollywood’s radar. But salvation came from an unexpected source. Josephine Dillon, the first wife of Clark Gable, worked at the station staging programs for local broadcast. She urged Fidler to exploit his insider knowledge of the film industry to become a gossip commentator for local radio. Fidler started by partnering with actor and singer Russ Columbo on early programs, but Columbo died before their shows gained traction with audiences.

Fidler proved a natural for radio. He kept his southern accent, but delivered the news in a high-pitched, intense voice. There was an element of Walter Winchell’s rat-a-tat-tat delivery, but his Tennessee tone gave his own speech a familiarity to his audience.

His most intense period occurred between 1936 and 1940 as his audience grew. He syndicated his “Jimmie Fidler’s Hollywood” column, and by 1940 he had regular broadcasts on Tuesday and Friday evenings. His column appeared in 150 newspapers. He demanded from his operatives that every piece of gossip be authentic and verifiable.

His signature sign-off after each broadcast was “Good night to you, and you, and I do mean you!” He also established his trademark four-bell rating system with four bells as a superb movie to one bell for a poor effort. However, he quickly gained a reputation for trashing more movies than liking them.

To set himself apart from Parsons and Hopper, Fidler began penning “open letters” to film stars that became more strident and scolding as he grew more popular among his readers and listeners.

He scolded Alice Faye for her failure to show up at promotional events in Pittsburgh, although she was laid low by illness. George Brent received a lecture for stringing along Ann Sheridan. He told Martha Raye to stay out of nightclubs and chastised Ginger Rogers for being a snob while in Hawaii. Constance Bennett sued Fidler for libel after he wrote that she snubbed Patsy Kelly on the Hal Roach lot. He also offered unsolicited advice how to cut actors’ salaries and which movies to produce.

While studio execs and actors chafed at Fidler’s sharp tongue, he commanded a large audience. Studios loaned him stars to accompany him on public appearances. The legendary 20th Century-Fox press agent Harry Brand introduced him to the right people to keep his column and broadcast fresh with new and interesting people.

His strained relationship with the studios and stars came to a head in the summer of 1941 when he was called to testify before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee Hearings on Motion Picture and Radio Propaganda.

The subcommittee, led by Sen. Gerald Nye (D-North Dakota) and Sen. D. Worth Clark (D-Idaho), was formed to determine whether Hollywood was making propaganda films to incite war-mongering to draw the United States into war.

Isolationists supporting the investigation alleged that films like “Confessions of a Nazi Spy” (1939), “Sergeant York” (1941) and “Dive Bomber” (1941) manipulated moviegoers with anti-Nazi messages. Warner Bros., with its reputation for producing movies with social messages, led the film industry with pictures that clearly cast Americans and Britons on the side of right fighting ruthless Nazis thugs.

Presenting himself as an expert witness, Fidler testified that Hollywood indeed was producing “hate-breeding” movies. He said he believed that Hollywood was too anti-Nazi.

His testimony raised the hackles of studio executives, but Fidler broadened his attacks to allege that filmmakers attempted to bribe him to write favorable reviews. But when pressed by Nye and Clark, he could only come up with two examples in which one did not look like a bribe at all.

Fidler said that Harry Brand offered to pay him $3,000 to produce a trailer for the Charlie Chan series and publicist Russell Birdwell offered the columnist $3,500 to write a favorable review for “The Prisoner of Zenda” (1937). Birdwell vehemently denied the allegation and offered to provide his own testimony at the hearing.

The Hollywood film industry was a clannish lot and fiercely protective of their own. Sensitive to charges of anti-Americanism and corruption, industry leaders – the talent and executives – viewed Fidler’s testimony as betrayal. Film trade publications howled with indignation. Editors penned their own “open letters” to Fidler, mocking him, his southern roots and his troubled history with film stars, citing him as the “most hated man in Hollywood.” Fidler’s second wife, Roberta “Bobbie” Law, who designed gowns for actresses, also received a spanking in the trade media.

An editor of one trade publication wrote: “For a long time now there has existed a deep and bitter hatred between Hollywood and its most obstreperous gossiper. A feud so deeply buried under the surface jollities and politeness that only recently, when Hollywood felt that Fidler had turned Judas on them, did it erupt in the open and spill its fire.”

When Fidler returned to Los Angeles, he encountered Errol Flynn one night at the Macambo nightclub. Flynn reportedly said, “You should be run out of Hollywood.” Flynn then punched Fidler in the face and Roberta Law responded by stabbing Flynn in the neck with a fork.

Flynn later described Fidler to reporters as a “contemptible liar.”

MGM Publicity Director Howard Dietz said, “Fidler is a congenital liar and it would be going against his conscience to tell the truth. I make it a point never to mention or think about Fidler.”

It’s not a stretch, certainly in the 1920s and 1930s, to believe that studio press agents paid for positive film reviews. Most newspaper reporters covering Hollywood knew how the system worked and likely had at least one encounter with an agent offering a handful of cash in exchange for favorable publicity. Fidler simply broke the unwritten code.

Trade publications widely circulated this photo of Fidler mopping his brow, implying he was nervous over his senate testimony. He wasn’t.

He felt no remorse and often aired his pet peeves about the industry. He disliked double features, extragavence on studio lots and propaganda pictures. What defined propaganda in his mind appeared to be rather broad, but he found preaching on any level unacceptable entertainment.

In his defense, Fidler wrote: “There are often hurt feelings because I speak and write frankly. Most of Hollywood – that part of Hollywood which hates me – can’t stand criticism. On many occasions, representatives of certain motion-picture companies have threatened to withdraw advertising unless my column was thrown out or my blunt opinions blue-penciled by editors. It is to the credit of the American press that in almost all instances, editors have told these representatives off.”

Los Angeles Times editors responded by ordering an audit of Fidler’s past columns to determine accuracy and promised to closer scrutinize his work.

Fidler could afford not to care about the industry’s reaction to his testimony. Unlike Parsons and Hopper, he did not need studios’ blessings to write and broadcast gossip that was often managed by studio brass. Newspapers and radio stations paid his salary, which was in the neighborhood of $225,000 a year. A national soap company paid him $3,500 a week to hawk their product.

At his peak in the late 1940s, he broadcast on 486 radio stations and was heard by 40 million people. His gossip columns appeared in 360 newspapers. He owned 11,000 shares of stock in Warner Bros. and 4,000 shares of 20th Century-Fox stock.

But unlike Parsons and Hopper, he no longer visited studio lots often after 1941. He left information gathering to an army of secretaries and production crew members paid generously for snippets of gossip.

Still, his credibility suffered. He alleged to the senate subcommittee that studio executives attempted to censor his column and broadcasts while at the same time demanding that Hollywood be censored for producing anti-Nazi films.

Fidler responded to his critics by noting that, “I did it for Hollywood’s own good as Hollywood is now learning. I am not pro-Nazi and I am not pro-British. I am fully, entirely, and only pro-American.”

He later slightly backtracked, but couldn’t help give another lecture and reinforce the perception that he was soft on Nazis: “Hollywood did take too many side digs at Nazism. I fail to see why Washington stuck its nose in Hollywood’s business. The senate has no right to censor pictures. I don’t like all the political fuss; I am sure public reaction has taught Hollywood its mistake.”

His position on the portrayal of Nazis is troubling. It doesn’t take a student of foreign policy to recognize the horrendous transgressions Germany took by invading Poland and France and the signing the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. International condemnation swiftly followed. Warner Bros.’ treatment of Nazi characters in films garnered considerable support. And contrary to Fidler’s testimony that these films lost money at the box office, most turned a nice profit. The hearings ended with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Fidler never received the lavish and friendly publicity from the trade publication that he once enjoyed before his testimony. While his audience remained strong, the Hollywood elite virtually ignored him.

A contract he signed in 1938 to appear in three films that would result in a $225,000 paycheck and an option for three more pictures within five years was never fulfilled. He appeared in “Garden of the Moon” (1938), but not another film until 1947 when he was cast in a cameo alongside Parsons and Hopper in “The Corpse Came C.O.D.”

For two seasons in 1952-53, he hosted “Hollywood Opening Night,” a live television program, but his postwar appearances in front of the camera for the most part were virtually non-existent.

Although he maintained his gossip column and radio shows, his roster of radio stations dropped to about 165 by 1956. He then turned his attention more to the business side of media. He was the chief executive officer of Texas International in 1956. The new company focused on television and film production in the Dallas-Ft. Worth area. In 1962, he was promoted to business editor at WORL radio, where he had a long association.

At the age of 48, Fidler married for the third time on June 6, 1947, to Adeline Cox McKnight, a 25-year-old former airline flight attendant. They had three daughters. One daughter, Julie Lorraine, died at the age of 3 in 1956. The couple divorced in 1960, and Fidler remarried a fourth time.

Fidler lived most of his adult life at his Toluca Lake home where he died in 1988.

Jimmie Fidler Internet Movie Database Biography

PERIODICALS, BOOKS and DOCUMENTS:

Silver Screen, February 1931

Modern Screen, December 1931

Radio Mirror, August 1937

Radio Mirror, October 1937

Broadcasting, April 1, 1938

Radio Mirror, August 1938

Silver Screen, March 1939

The Film Daily, Aug. 19, 1941

Milwaukee Journal, Sept. 8, 1941

The Film Daily, Sept. 10, 1941

Motion Picture Daily, Sept. 16, 1941

Showman’s Trade Review, Oct. 4, 1941

Modern Screen, November 1941

Hollywood, December 1941

Radio & Television Mirror, July 1942

Photoplay, October 1942

Broadcasting, March 19, 1956

Broadcasting, Aug. 20, 1956

Broadcasting, Oct. 2, 1962

Los Angeles Times, Aug. 11, 1988

Celluloid Soldiers: Warner Bros.’s Campaign Against Nazism, by Michael E. Birdwell (NYU Press), 2000

The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960, by Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund (University of Illinois Press), 2003

Hollywood’s America: Twentieth-Century America Through Film, edited by Steven Mintz, Randy W. Roberts (John Wiley & Sons) 2010

James Marion Fidler, Ancestry.com (accessed Sept. 18, 2014)

1910 United States Federal Census

1920 United States Federal Census

1930 United States Federal Census

Lia Torá: Worst Timing Ever

Lia Torá, a beauty and celebrated dancer in Spain and her native Brazil, may go down in cinematic history as arriving in Hollywood at the very moment her brand of talent became obsolete.

Fluent in Spanish, Portuguese and French, but hardly speaking a word of English, she arrived in New York City on Sept. 13, 1927, en route to Hollywood to begin a career as an actress. Three weeks later, “The Jazz Singer” premiered and overnight the need for silent film Latin bombshells was relegated to the dustbin.

Latin actors were de rigueur in Hollywood following the whopping success of Rudolph Valentino and Gilbert Roland. And film studio press agents were not particularly interested in actors’ ethnic backgrounds, lumping anyone’s name that ended with a vowel into the category of Latin lover.

If Torá had mastered English before her arrival, she very well could have had a career that would rival Dolores del Rio, Rita Hayworth, Dolores Costello and even the comedienne Lupe Velez. Her future likely would have taken a different route.

Rather, Lia Torá gained infamy as a suspected Nazi, or at the very least a fascist, who may have been complicit in a conspiracy to overthrow the Brazilian government in May 1938.

Torá’s role in the messy affair is murky, but it overshadowed her more positive contributions as an early female pioneer in auto racing and effectively ended a promising future in entertainment and on the race circuit.

Born Horácia Corrêa D’Ávila on May 12, 1907, in the São Cristóvão neighborhood of Rio de Janerio to Portuguese and Spanish parents, Torá was sent to Spain to study dance at the Dance Academy of Barcelona. When she was 18, she returned to Brazil as a dancer for the Velasco Dance Company where she gained considerable attention for her fluid dancing.

In late 1924, she met Julio De Moraes, a Brazilian newspaperman and son of Viscount De Moraes, an immensely wealthy Portuguese immigrant who made his fortune in Brazil. De Moraes was 26 years Torá’s senior, married and had a son. But Torá and De Moraes flouted the social mores of the predominately Catholic country and wed. In 1925, twins Marie Julio and Julio Mario were born.

Independent, intelligent and ambitious, Torá had hoped to capitalize on her popularity as a dancer by transitioning to a lucrative movie career. A year after her children were born, Torá entered a contest sponsored by Fox Films’ foreign offices, which was looking for new talent from Brazil, Spain and Italy. The prize was an expense-paid trip to Hollywood and a film contract. Torá won the contest only after Egyptian expatriate Eva Nil was disqualified for not being a native Brazilian.

De Moraes objected to Torá going to Hollywood as a contest winner. Screenland magazine reported that Torá, in fact, had rejected the prize and wanted the contract based on her own merits.

Whatever the case, Torá arrived in New York in September 1927, and took the train to Los Angeles.

Torá was a striking woman, with dark brown hair, olive skin and brilliant green eyes. Yet Fox executives didn’t know what to make of her or how to best use her talents. It may have been at this point that the studio lost interest in Torá as it geared up for sound.

However, director Wallace MacDonald cast her in the comedy “The Low Necker” (1927) featuring Marjorie Beebe and Trixie the Horse. Fox released the film just three moths after Torá’s arrival in the United States. The fledgling actress was then virtually idle for a year aside from some bit parts before appearing in a small role as a girlfriend in “Making the Grade” (1929).

Frustrated, Torá co-scripted with De Moraes and Douglas Z. Doty “The Veiled Woman” (1929) and featuring Paul Vincent and Bela Lugosi. The plot focused on Torá’s character who rescues a young woman from a notorious womanizer. She then tells the young woman of the men in her own life, including one lover who left her because of her history with men and a Briton who was a gambler and seducer, but also her true love.

The film garnered tepid reviews. Daily Variety, misidentifying the film as “Veiled Lady,” noted that the movie would be remembered for its unfamiliar actors and it would play better in the overseas market. The film was silent, although Fox had considered inserting talking sequences to widen its appeal.

When Fox decided not to renew Torá’s contract, she formed Brasilian Southern Cross Productions and set up offices at Tec-Art Studios on Melrose Avenue. The new production company’s first project was “Mary, the Beautiful” (possibly retitled “Soul of a Peasant”) with De Moraes directing and Torá in the lead role. But the production company did little after its initial film.

After working briefly for Universal on the film “Don Juan Diplomático” (1931) and earning third billing, she returned to Fox to film the Spanish-language version of “Charlie Chan Carries On” (“Eran Trece”), which was released in December 1931.

Torá never mastered English. Her efforts to produce quality Spanish-language films through Brasilian Southern Cross failed, and Fox’s lukewarm relationship with her effectively put an end to her American acting career by 1932.

She returned to Rio de Janerio and began to indulge in auto racing, usually joining her husband as a co-driver and navigator. A year after her return to Brazil, organizers of the Grand Prix Cidade de Rio de Janeiro mapped the Gávea Circuit, better known to drivers as “The Devil’s Springboard.” South American motorsport, with its mountainous terrain, rough roads and roadside cliffs that dropped into vast valleys, was a dangerous endeavor for any race driver. The European circuits paled in comparison.

The 279-kilometer Gávea Circuit had 101 curves with many tight hairpins that challenged the courage of any driver. Steep slopes gave way to deep dives on roads that varied from sand to cement to asphalt. The debut race on Aug. 8, 1933, ended with no injuries.

However, for the Oct. 3, 1934, event, Nino Crespi, driving a Bugatti T37A, crashed into a pole on the 25th lap. Both of his legs were crushed. They were amputated, but he died at the hospital. Crespi’s mechanic had his left foot crushed and it also was amputated.

De Moraes, behind the wheel in a Chrysler Adaptado, flipped his car on the sixth lap. Torá, riding in the passenger seat, was seriously injured, but she recovered. Driver Irineu Correa won the race in 3 hours, 56 minutes and 23 seconds in a Ford V-8 Adaptado.

Four years later Torá’s auto racing career effectively came to an end with her arrest on charges of conspiracy to overthrow the government of President Getúlio Vargas.

With the rise of Nazi Germany in the mid-1930s, Germans in Brazil formed the Integralista, an organization of intellectuals and artists, along with bankers and industrialists, to support a fascist agenda. Taking cues from fascist regimes in Germany and Italy, street brawls and thuggery erupted throughout Brazil, especially in Rio de Janerio with many conflicts between the Communist Party of Germany and the National-Socialist German Workers’ Party.

On May 11, 1938, the Integralists orchestrated an uprising, later known as the “Pajama Putsch.” The overthrow attempt failed and police rounded up more than 1,000 civilians and nearly 500 military men. About 600 were released, but the National Security Tribunal tried the remaining participants. Among them were Torá and De Moraes.

The court convicted De Moraes of participating in the revolt, but it found Torá not guilty of conspiracy to overthrow the government on March 1, 1939. Yet the evidence was damning. Belmiro Valverde, one of the ringleaders of the revolt, was arrested at Torá’s home and law authorities seized a large quantity of dynamite from his car. He was also convicted on charges stemming from the uprising.

De Moraes continued to race at least through 1941. He died in 1956 at the age of 75. Torá appeared in one more movie, “The Confessions of Frei Pumpkin” (1971), a Brazilian production. She died in May 27, 1972.

Lia Torá Internet Movie Database Biography

SOURCES and BOOKS:

Vida Doméstica, August 1924

Motion Picture Classic, September 1927

Motion Picture Classic, October 1928

The Evening Independent, Sept. 8, 1928

The Evening Independent, Nov. 22, 1928

Picture Play Magazine, 1929

Reading Eagle, June 30, 1929

Reading Times, July 2, 1929

Screenland, October 1929

Cine-Mundial, February 1931

Cine-Mundial, June 1932

The Milwaukee Journal, Oct. 4, 1934

The New International Year Book, 1938

Mexia (Texas) Weekly Herald, May 20, 1938

Sarasota Herald-Tribune, March 2, 1939

San Bernardino County Sun, March 2, 1939

Tuscaloosa News, March 30, 1943

Vargas of Brazil: A Political Biography by John W. Dulles (University of Texas Press), 1967

Autos and Progress: The Brazilian Search for Modernity by Joel Wolfe (Oxford University Press), 2009

Muheres do Cinema Brasileiro (accessed Sept. 10, 2014)

The Wagner Boys

EDITOR’S NOTE: Welcome to Hollywood Oblivion, the website dedicated to documenting and preserving the work of film production crews who labored anonymously behind the camera and the actors who rarely earned screen credits. For our debut post, we look at the work of brothers Jack, Blake, Bob and Max Wagner. We will post regularly, but not on a schedule, so please sign up for our email notifications.

Hollywood’s enduring legacy is its love for its royalty. And without family dynasties the film industry might just be a little less interesting and less illustrious.

Even in its infancy, the film industry had affection for movie-making families. Nepotism was perfectly acceptable, if not encouraged. Directors, actors, writers and cinematographers brought in brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, and distant cousins to satisfy the expanding hunger for more talent to keep up the hectic pace of filmmaking.

The Wagner family, though hardly royalty, nonetheless had a remarkable run in Hollywood from 1910 to 1975, working in front or behind the camera in nearly 800 films and television episodes. Known as the Wagner Boys, and to their intimates the Mexican Wagners because they grew up in Mexico, they had worked on most of the studio lots. They hardly qualified as a dynasty and their influence probably extended no further than the end of DeLongpre Avenue in the heart of Hollywood, where they lived in an enclave presided over by their mother, Edith. With the exception of perhaps Bob, a family man, the other boys – Jack, Blake and Max – were a hard-drinking and brawling bunch.

Jack’s wife, Winifred, once sought a divorce after he spanked her in front of his drinking buddies because there was no liquor in the house. He also was once involved in an alcohol-fueled brawl at a Hollywood speakeasy in March 1927 that led to the stabbing death of actor Eddie Diggins. Police suspected a bootlegger, Charles Meehan, of the stabbing but never charged him with a crime. A month later, Max witnessed his roommate, actor Paul Kelly, beat to death Ray Raymond, the husband of actress Dorothy Mackaye, following a night of drinking.

The oldest brother, Jack, started his career as a furniture painter and prop man for D.W. Griffith and then moved to cameraman and writer. Blake was a cameraman for most of his career, working for Fox Studios and on the Mack Sennett and Hal Roach lots. His twin brother Bob worked a decade or so as an assistant cameraman for First National Pictures. The baby of the family, Max, was a prolific “day” actor. He appeared in more than 400 movies and nearly 200 television episodes spanning six decades.

The brothers often crossed paths, helped each other find film work and occasionally collaborated on projects. Today, they are a footnote in Hollywood history. But during their day the Wagners were an uncredited yet necessary cog in the filmmaking machinery that produced the likes of “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “The Dawn Patrol” and countless Sennett and Roach comedies. Ever wonder how the Keystone Kops, Bev Bevan, Ben Turpin and Harry Langdon pulled those stunts? More than likely there was a Wagner behind it.

JACK WAGNER

(1891-1963)

When Jack’s father, William, lost his Southern Pacific railroad job in 1895, the Wagner family headed for Torreon, Mexico, where he found a conductor’s job on the railroad. Jack was 4 years old when he arrived in Mexico. At the age of 19, when the Mexican revolution erupted in 1910, Jack returned to Los Angeles and found work painting furniture, moving props and earning $4 a day as an extra for D.W. Griffith.

Griffith allowed him to do some assistant camera and second unit work, but Jack found that comedy suited him. He joined Mack Sennett in 1913 as a cameraman and gag writer. Comedy construction was his métier as he found ways to stage automobile accidents and train wrecks without killing the actors. His subtle gags were just as effective as the slapstick. For Chester Conklin, Jack wrote a brief scene depicting Conklin as a penny-pinching miser by having Conklin to go his bedroom closet to dust off his best dress suit wrapped in yellow and brittle newspaper with the headline “Dewey Captures Manila.”

Jack Wagner, right, with his brother, Blake, served as combat photographers in France during World War I. (Photo: Wagner Family Collection)

He switched to Fox Studios as a cameraman, but when war broke out in 1917, he enlisted to serve as a cameraman for the American Expeditionary Forces’ first motion picture camera unit. Attached to the Air Corps, he documented their exploits, then covered the ground war at the Marne, St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne.

Jack returned to Hollywood following his discharge from the Army in 1919 with his first assignment writing gags, filming and working as an assistant director for the Hall Room Boys Photoplays under the supervision of Harry Cohn. The Hall Room Boys series featured Edward Flanagan and Neely Edwards and based on the popular newspaper comic strip of the era.

He continued writing comedy bits for the Hall Room Boys, but in between assignments took on assistant director duties for Allan Dwan on “The Forbidden Thing” (1920) and “The Scoffer” (1920) and for Arthur Rosson on “A Splendid Hazard” (1920). But it was comedy that paid the bills and Jack signed contracts with Mack Sennett in his second go-around with the producer and with Hal Roach.

By the second half of the 1920s, he was working on larger productions. He signed a contract with Warner Bros. and joined the writing staff for John Barrymore’s “The Sea Beast” in 1926. He also established a working relationship with director Richard Wallace, writing scenes for “Syncopating Sue” (1926) featuring Corinne Griffith and a screen adaptation for “McFadden’s Flats” (1927).

Yet, like many silent comedy film writers, sound was not kind. Jack struggled to move from the physical and visual aspect of comedy to dialogue. But 1930 started promising when Fox Studios created its Foreign Department in July to produce Spanish-language versions of popular English-language films. Director James Tinling headed the department and recruited the Spanish-speaking Jack and writers Dave Howard and Dick Harlan. Paramount and Universal also opened similar departments that would rival Fox for the Latino audience.

Paramount attracted actors Ramón Pereda and Antonio Moreno in 1930 for “El Cuerpo del Delito” with Jack on board as assistant director. Over at Fox, he had directing duties for “Entre Platos y Notas” (1930) and “Cupido Chauffeur” (1930) and both starring Manuel Arbó.

Jack Wagner, center, on the set of The Litltle Minister (1934) with Katharine Hepburn and Richard Wallace, right. (Photo: R. Wallace Estate)

But the studios failed to support the departments. While foreign projects for the studios began with high hopes, the desire to economize and streamline productions for both the English and Spanish versions left the Spanish films the stepchild of the studios. Studios shot the English versions during the day and the Spanish films at night. Quality between the two versions was dramatic as the executives continued to trim Spanish-language film budgets. By 1932, the studios were scaling back production and eventually shuttered their foreign departments.

Jack continue with odd jobs, providing Richard Wallace with additional dialogue on “The Little Minister” in 1934 and writing one-liners for Mae West in her films. He was a director’s “what-if” man. “What if Mae did this” and “What if Mae did that.” The director worked sight gags and bits of dialogue into the script during shooting.

Through the late 1930s, his output was inconsistent and relegated mostly to “B” productions. As World War II drew to a close, Jack had a story rattling around in his head that he thought would make an excellent film. It was the story of a young, unseen Latino, Benny Martin, living in a small town and largely ignored by his neighbors. But the city leaders deem Benny a war hero following his death in combat during the war. The town fathers scheme to exploit the tragedy to put their community on the map. They convince Benny’s father to move from his shack to a nice home while they stage a publicity campaign claiming that Benny had come from proud Spanish lineage. The town leaders’ hypocrisy is exposed when a military entourage arrives in town to present a medal to the father and concludes with an emotional speech from the father about his son.

Years of slapstick comedy writing failed to prepare Wagner for the discipline required to write a full script. Every studio in town rejected his pitch. He finally sought the help of John Steinbeck, Max’s boyhood friend who grew up listening to Jack and Max’s mother, Edith, tell stories about her experiences in Mexico. Edith also had been Steinbeck’s early writing coach and sounding board for Steinbeck’s story ideas while living in Salinas. Steinbeck and Wagner never collaborated on a project, but Jack was desperate to get the film, “A Medal for Benny,” off the ground. The Steinbeck name was box-office magic and Paramount agreed to produce the film on the condition that Steinbeck co-write the script.

“A Medal for Benny,” featuring Dorothy Lamour, Arturo de Córdova and J. Carrol Naish, opened on April 16, 1945, to good reviews. Naish was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Support Actor (losing to James Dunn in “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn”) and Steinbeck and Wagner received Academy nods for Best Original Story (losing to Charles G. Booth for “The House on 92nd Street”).

Jack could never match his success with “A Medal for Benny.” But he frequently traveled to Mexico, joining Steinbeck on one occasion to provide additional dialogue for “The Pearl” and producing Mexican films, including “La Otra” (“The Other”), starring Dolores del Rio.

In 1955, Jack penned with Bert Hackle an original story, “A Machine for Chuparosa,” about a father and daughter dispatched by their neighbors in a small Mexican village to Mexico City to buy a machine to modernize their community. Wagner and Hackle wrote the story for director Robert Aldrich, who had an option on it. Aldrich submitted a final screenplay by Teddi Sherman in December 1956 with the intent to start filming. Principal shooting was scheduled for early 1957 in Mexico with Dean Martin tapped as the film’s star. However, Aldrich allowed the rights to the screenplay to revert to Sherman. The film never got off the ground, but it was revived on several occasions over the next seven years with Clint Walker, Jeffrey Hunter, John Wayne and Burt Lancaster attached as leads at different times. The screenplay remains unproduced.

BLAKE WAGNER

(1892-1957)

Blake Wagner’s career closely paralleled his older brother Jack’s at least until Jack drifted from camera work to writing gags and working as an assistant director. Blake served his time doing grunt work for D.W. Griffith and graduated to assistant cameraman before joining his brother at Mack Sennett’s lot.

A directing stint followed in 1915 at Reliance-Majestic Studios, but any evidence to date of his films there has apparently been lost to time. By 1917, he joined Jack at Fox Studios shooting Sunshine Comedies featuring Chester Conklin and an unusual western comedy vehicle for Tom Mix titled “Six-Cylinder Love” (1917).

The stint at Fox gave Blake much more to work with than at the Sennett lot. Fox’s deep pockets financed quality production values, special effects and complex gags.

Blake then enlisted in the U.S. Army Signal Corps on Sept. 17, 1917. As a member of the Army’s first motion picture unit, he went to France to document land and air engagements.

Following his discharge as a private first class on July 21, 1919, he returned to Fox, this time behind the camera for the Hall Room Boys Photoplays film “The Chicken Hunters” (1919) and “Hired and Fired” (1920) among other shorts. He often partnered with Jack. His tenure at Fox acquainted him with Eddie Cline, Roy Del Ruth and Harry Sweet who called on him throughout the ’20s to shoot for them.

But for every Sunshine or Hall Room Boys two-reeler there were some true – and literally – dogs to film. Century Films specialized in animal shorts, including Brownie the Dog, a somewhat low-rent Rin Tin Tin. Century tasked Blake with shooting “Just Dogs” (1922), one of several shorts featuring the Century Dogs. Fifty dogs of assorted breeds had fought constantly forcing Blake and the director, Albert Herman, to extend the shooting schedule by eight weeks.