EDITOR’S NOTE: Welcome to Hollywood Oblivion, the website dedicated to documenting and preserving the work of film production crews who labored anonymously behind the camera and the actors who rarely earned screen credits. For our debut post, we look at the work of brothers Jack, Blake, Bob and Max Wagner. We will post regularly, but not on a schedule, so please sign up for our email notifications.

Hollywood’s enduring legacy is its love for its royalty. And without family dynasties the film industry might just be a little less interesting and less illustrious.

Even in its infancy, the film industry had affection for movie-making families. Nepotism was perfectly acceptable, if not encouraged. Directors, actors, writers and cinematographers brought in brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, and distant cousins to satisfy the expanding hunger for more talent to keep up the hectic pace of filmmaking.

The Wagner family, though hardly royalty, nonetheless had a remarkable run in Hollywood from 1910 to 1975, working in front or behind the camera in nearly 800 films and television episodes. Known as the Wagner Boys, and to their intimates the Mexican Wagners because they grew up in Mexico, they had worked on most of the studio lots. They hardly qualified as a dynasty and their influence probably extended no further than the end of DeLongpre Avenue in the heart of Hollywood, where they lived in an enclave presided over by their mother, Edith. With the exception of perhaps Bob, a family man, the other boys – Jack, Blake and Max – were a hard-drinking and brawling bunch.

Jack’s wife, Winifred, once sought a divorce after he spanked her in front of his drinking buddies because there was no liquor in the house. He also was once involved in an alcohol-fueled brawl at a Hollywood speakeasy in March 1927 that led to the stabbing death of actor Eddie Diggins. Police suspected a bootlegger, Charles Meehan, of the stabbing but never charged him with a crime. A month later, Max witnessed his roommate, actor Paul Kelly, beat to death Ray Raymond, the husband of actress Dorothy Mackaye, following a night of drinking.

The oldest brother, Jack, started his career as a furniture painter and prop man for D.W. Griffith and then moved to cameraman and writer. Blake was a cameraman for most of his career, working for Fox Studios and on the Mack Sennett and Hal Roach lots. His twin brother Bob worked a decade or so as an assistant cameraman for First National Pictures. The baby of the family, Max, was a prolific “day” actor. He appeared in more than 400 movies and nearly 200 television episodes spanning six decades.

The brothers often crossed paths, helped each other find film work and occasionally collaborated on projects. Today, they are a footnote in Hollywood history. But during their day the Wagners were an uncredited yet necessary cog in the filmmaking machinery that produced the likes of “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “The Dawn Patrol” and countless Sennett and Roach comedies. Ever wonder how the Keystone Kops, Bev Bevan, Ben Turpin and Harry Langdon pulled those stunts? More than likely there was a Wagner behind it.

JACK WAGNER

(1891-1963)

When Jack’s father, William, lost his Southern Pacific railroad job in 1895, the Wagner family headed for Torreon, Mexico, where he found a conductor’s job on the railroad. Jack was 4 years old when he arrived in Mexico. At the age of 19, when the Mexican revolution erupted in 1910, Jack returned to Los Angeles and found work painting furniture, moving props and earning $4 a day as an extra for D.W. Griffith.

Griffith allowed him to do some assistant camera and second unit work, but Jack found that comedy suited him. He joined Mack Sennett in 1913 as a cameraman and gag writer. Comedy construction was his métier as he found ways to stage automobile accidents and train wrecks without killing the actors. His subtle gags were just as effective as the slapstick. For Chester Conklin, Jack wrote a brief scene depicting Conklin as a penny-pinching miser by having Conklin to go his bedroom closet to dust off his best dress suit wrapped in yellow and brittle newspaper with the headline “Dewey Captures Manila.”

Jack Wagner, right, with his brother, Blake, served as combat photographers in France during World War I. (Photo: Wagner Family Collection)

He switched to Fox Studios as a cameraman, but when war broke out in 1917, he enlisted to serve as a cameraman for the American Expeditionary Forces’ first motion picture camera unit. Attached to the Air Corps, he documented their exploits, then covered the ground war at the Marne, St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne.

Jack returned to Hollywood following his discharge from the Army in 1919 with his first assignment writing gags, filming and working as an assistant director for the Hall Room Boys Photoplays under the supervision of Harry Cohn. The Hall Room Boys series featured Edward Flanagan and Neely Edwards and based on the popular newspaper comic strip of the era.

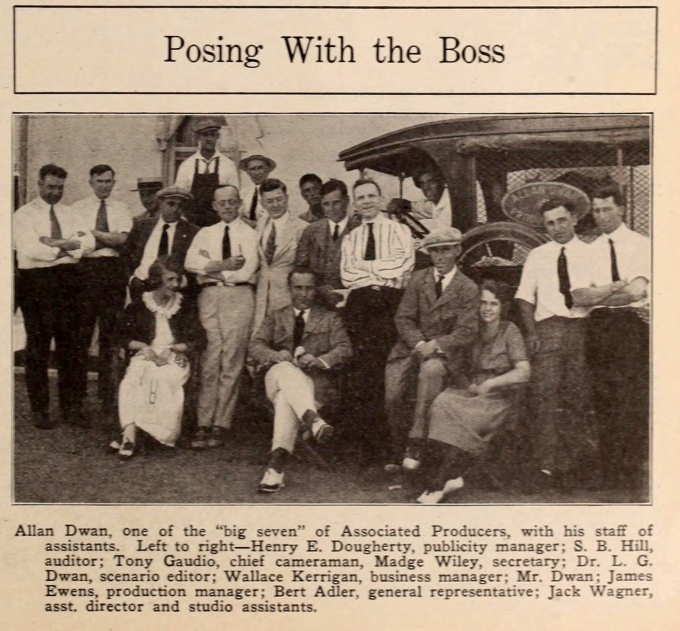

He continued writing comedy bits for the Hall Room Boys, but in between assignments took on assistant director duties for Allan Dwan on “The Forbidden Thing” (1920) and “The Scoffer” (1920) and for Arthur Rosson on “A Splendid Hazard” (1920). But it was comedy that paid the bills and Jack signed contracts with Mack Sennett in his second go-around with the producer and with Hal Roach.

By the second half of the 1920s, he was working on larger productions. He signed a contract with Warner Bros. and joined the writing staff for John Barrymore’s “The Sea Beast” in 1926. He also established a working relationship with director Richard Wallace, writing scenes for “Syncopating Sue” (1926) featuring Corinne Griffith and a screen adaptation for “McFadden’s Flats” (1927).

Yet, like many silent comedy film writers, sound was not kind. Jack struggled to move from the physical and visual aspect of comedy to dialogue. But 1930 started promising when Fox Studios created its Foreign Department in July to produce Spanish-language versions of popular English-language films. Director James Tinling headed the department and recruited the Spanish-speaking Jack and writers Dave Howard and Dick Harlan. Paramount and Universal also opened similar departments that would rival Fox for the Latino audience.

Paramount attracted actors Ramón Pereda and Antonio Moreno in 1930 for “El Cuerpo del Delito” with Jack on board as assistant director. Over at Fox, he had directing duties for “Entre Platos y Notas” (1930) and “Cupido Chauffeur” (1930) and both starring Manuel Arbó.

Jack Wagner, center, on the set of The Litltle Minister (1934) with Katharine Hepburn and Richard Wallace, right. (Photo: R. Wallace Estate)

But the studios failed to support the departments. While foreign projects for the studios began with high hopes, the desire to economize and streamline productions for both the English and Spanish versions left the Spanish films the stepchild of the studios. Studios shot the English versions during the day and the Spanish films at night. Quality between the two versions was dramatic as the executives continued to trim Spanish-language film budgets. By 1932, the studios were scaling back production and eventually shuttered their foreign departments.

Jack continue with odd jobs, providing Richard Wallace with additional dialogue on “The Little Minister” in 1934 and writing one-liners for Mae West in her films. He was a director’s “what-if” man. “What if Mae did this” and “What if Mae did that.” The director worked sight gags and bits of dialogue into the script during shooting.

Through the late 1930s, his output was inconsistent and relegated mostly to “B” productions. As World War II drew to a close, Jack had a story rattling around in his head that he thought would make an excellent film. It was the story of a young, unseen Latino, Benny Martin, living in a small town and largely ignored by his neighbors. But the city leaders deem Benny a war hero following his death in combat during the war. The town fathers scheme to exploit the tragedy to put their community on the map. They convince Benny’s father to move from his shack to a nice home while they stage a publicity campaign claiming that Benny had come from proud Spanish lineage. The town leaders’ hypocrisy is exposed when a military entourage arrives in town to present a medal to the father and concludes with an emotional speech from the father about his son.

Years of slapstick comedy writing failed to prepare Wagner for the discipline required to write a full script. Every studio in town rejected his pitch. He finally sought the help of John Steinbeck, Max’s boyhood friend who grew up listening to Jack and Max’s mother, Edith, tell stories about her experiences in Mexico. Edith also had been Steinbeck’s early writing coach and sounding board for Steinbeck’s story ideas while living in Salinas. Steinbeck and Wagner never collaborated on a project, but Jack was desperate to get the film, “A Medal for Benny,” off the ground. The Steinbeck name was box-office magic and Paramount agreed to produce the film on the condition that Steinbeck co-write the script.

“A Medal for Benny,” featuring Dorothy Lamour, Arturo de Córdova and J. Carrol Naish, opened on April 16, 1945, to good reviews. Naish was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Support Actor (losing to James Dunn in “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn”) and Steinbeck and Wagner received Academy nods for Best Original Story (losing to Charles G. Booth for “The House on 92nd Street”).

Jack could never match his success with “A Medal for Benny.” But he frequently traveled to Mexico, joining Steinbeck on one occasion to provide additional dialogue for “The Pearl” and producing Mexican films, including “La Otra” (“The Other”), starring Dolores del Rio.

In 1955, Jack penned with Bert Hackle an original story, “A Machine for Chuparosa,” about a father and daughter dispatched by their neighbors in a small Mexican village to Mexico City to buy a machine to modernize their community. Wagner and Hackle wrote the story for director Robert Aldrich, who had an option on it. Aldrich submitted a final screenplay by Teddi Sherman in December 1956 with the intent to start filming. Principal shooting was scheduled for early 1957 in Mexico with Dean Martin tapped as the film’s star. However, Aldrich allowed the rights to the screenplay to revert to Sherman. The film never got off the ground, but it was revived on several occasions over the next seven years with Clint Walker, Jeffrey Hunter, John Wayne and Burt Lancaster attached as leads at different times. The screenplay remains unproduced.

BLAKE WAGNER

(1892-1957)

Blake Wagner’s career closely paralleled his older brother Jack’s at least until Jack drifted from camera work to writing gags and working as an assistant director. Blake served his time doing grunt work for D.W. Griffith and graduated to assistant cameraman before joining his brother at Mack Sennett’s lot.

A directing stint followed in 1915 at Reliance-Majestic Studios, but any evidence to date of his films there has apparently been lost to time. By 1917, he joined Jack at Fox Studios shooting Sunshine Comedies featuring Chester Conklin and an unusual western comedy vehicle for Tom Mix titled “Six-Cylinder Love” (1917).

The stint at Fox gave Blake much more to work with than at the Sennett lot. Fox’s deep pockets financed quality production values, special effects and complex gags.

Blake then enlisted in the U.S. Army Signal Corps on Sept. 17, 1917. As a member of the Army’s first motion picture unit, he went to France to document land and air engagements.

Following his discharge as a private first class on July 21, 1919, he returned to Fox, this time behind the camera for the Hall Room Boys Photoplays film “The Chicken Hunters” (1919) and “Hired and Fired” (1920) among other shorts. He often partnered with Jack. His tenure at Fox acquainted him with Eddie Cline, Roy Del Ruth and Harry Sweet who called on him throughout the ’20s to shoot for them.

But for every Sunshine or Hall Room Boys two-reeler there were some true – and literally – dogs to film. Century Films specialized in animal shorts, including Brownie the Dog, a somewhat low-rent Rin Tin Tin. Century tasked Blake with shooting “Just Dogs” (1922), one of several shorts featuring the Century Dogs. Fifty dogs of assorted breeds had fought constantly forcing Blake and the director, Albert Herman, to extend the shooting schedule by eight weeks.

From Fox to free-lance assignments with Century, Blake then signed with Mack Sennett for the second time for a prolific period of filming Ben Turpin and Billy Bevan shorts. His most notable effort was “The Dare-Devil” (1923), co-scripted by his cousin, Rob Wagner, and Sennett with Del Lord at the helm. Turpin is a hapless wannabe actor roped into doing dangerous stunts by a demanding movie director played by Harry Gribbon. Ernie Crockett supervised the special effects, which resulted in a smooth transition between the setup of the physical action and resulting elaborate stunt.

By the beginning of 1924, both Blake and Jack jumped ship for Hal Roach Studios. Blake performed stock camera work, filling in with second unit duties, extra scenes or as a camera operator. He then performed consecutive principal filming for the Our Gang shorts “Seein’ Things,” “Commencement Day,” “Cradle Robbers,” “It’s a Bear” and fill-in work on other Our Gang shorts.

Following a two-year association with Monty Banks, camera work began to dry up as talkies asserted dominance. Blake had always maintained a good relationship with Fox and returned to the lot off and on to take on assistant cameraman duties, including “The Three Sisters” (1930) and “Tess of the Storm Country” (1932). However, by the end of 1932 he was out of work.

Yet Blake was versatile. He developed and held a patent for lighter makeup applications to give actors a more natural look under the harsh studio lights. He also developed lighting techniques that allowed the use of panchromatic film in low-light conditions.

He was also a devoted puppeteer often performing staged shows for children at Los Angeles area department stores and taking his show on the road in performances sponsored by the Richfield Co. (but always with a gasoline station or oil theme!). A product of the times, some of his characters – painted in blackface – were far from politically correct.

Blake Wagner, right, with brother Bob, center, staging a puppet show in 1933. (Photo: K.W. Starrett Collection)

Jack wrote the screenplay for the dark-themed short film “Strings” (1933), using Blake’s puppets as a plot device. The main character, a puppeteer, stages a show involving a love triangle and then goes home to find his wife involved in an identical situation with her lover. The husband is not interested in the affair until his wife attempts to destroy one of his puppets. He tries to shoot her only to accidentally kill himself.

Although Blake had a remarkable capacity for parties at night and be at the studio on time the next morning, he more or less settled down when he met Ruth Yeager Miller, a young starlet who had a small part as Zilah, a marriage market prospect, in “The Sheik” (1921) and a similar role in Cecil B. DeMille’s “The King of Kings” (1927).

The couple married on Dec. 14, 1927, at the Trinity Methodist Church in Los Angeles. Two children followed: Kim and Pamela. By 1934, Blake was producing short films for Paramount. But after 6-year-old Kim was killed by a truck while crossing the intersection at Sunset Boulevard and Highland Avenue in October 1934, the marriage fell apart. He later married Amelia Broening.

While 1940 census lists Blake as a “photographer” at a “motion picture studio,” there is little documentation of his work after 1932.

ROBERT “BOB” WAGNER

(1892-1950)

By the time Robert Hawley Wagner arrived in Hollywood in about 1926, he was married and had two young sons. Jack and Blake were veteran film men and even his younger brother, Max, was working as a character actor.

Bob was 20 years old when his father, William, died in 1912. As a train conductor, William during the Mexican revolution had squared off with rebels who attempted to hijack his train. He was critically wounded and the family took him to Los Angeles where he succumbed to his injuries. Jack and Blake were already in Los Angeles, and their mother took Max to Salinas.

Bob drifted, first living in New Orleans and later in Chicago before moving to Napanee, Canada, where he took a job as an assistant manager for the William Davies Co., a fish-packing company. In Napanee in 1917, he married Ida Beryl Lazier. In 1920, he returned to Chicago before settling for a brief period in Salinas to be near his mother and Max.

When he moved to Hollywood, he joined Local 659 and found work as a second unit cameraman and camera operator for First National Picture, later purchased by Warner Bros.

The smallest of the Wagner boys, Bob stood at 5 feet, 5 inches tall. His compact, gymnast body gave him agility that proved useful when camera work required filming in small places. He was adept to using the Akeley camera in aerial photography and scenes requiring quick reflexes. These traits gave him work on “The Sea Beast” (1926), which had some action sequences shot in tight quarters, and some trench scenes in “All Quiet n the Western Front” (1930). Directors also used Wagner to fold himself into a soundproof booth that encased the camera to minimize the machine’s noise during sound recording.

Bob Wagner, second from right, working as a second unit cameraman on the set of The Dawn Patrol (1930). (Photo: K.W. Starrett Collection)

During the final act for the James Cagney vehicle “The Public Enemy” (1931), Bob crammed himself under the floorboards of the set with his camera to film the scene in which the body of Cagney’s character falls face down virtually on top of the camera. He also taught Cagney how to tuck his knees to his chin to perform somersaults, a technique the actor used for most of his career. He also coached Paul Muni similar acrobatic tricks while a camera operator for “I Am a Fugitive from Chain Gang” (1932).

Bob Wagner with Thelma Todd, left, and Catherine Hunter, about 1931. (Photo: K.W. Starrett Collection)

First National laid off Bob around 1934. He managed free-lance work for a while, but by the late 1930s decided to return to Napanee. Both of his sons, Richard and William, enlisted in the military during World War II. Richard served as a U.S. Army captain in the Pacific Theater and William was a navigator/gunner in the Royal Canadian Air Force. William was killed in action on Feb. 21, 1945, while on a bombing raid over Germany.

MAX WAGNER

(1901-1975)

Maxwell Sergins Wagner had a fly-on-the-wall film career that gave him a balcony seat to witness virtually every milestone achieved in the film industry throughout the Golden Era. That doesn’t mean he stood out as a character actor among the ranks of Ian Wolfe, Paul Fix or Irving Bacon. But he managed to work steadily as a day actor ranging from appearing as background atmosphere to the occasional fourth and fifth billings as a henchman or bully. The standing joke in his family was if one took a one-minute snack break while watching one of his films on television, his entire performance would be missed.

The Los Angeles Daily News columnist Matt Weinstock summed up Max’s career this way in 1943: “All gangster pictures have a scene in which the villains close in on the hero. A door opens and gangster No. 1 smirks in the room. Behind him is gangster No. 2, who sands at this side and says, ‘Okey, boss.’ Gangster No. 3 takes a position to the left. Gangster No. 4 closes the door behind him and leans against it menacingly. For years Max was No. 4. One day he was promoted to No. 3. It was a great day on Vine st.”

Max’s tough looks and broad chest and shoulders typecast him as henchmen, convicts, truck drivers and mechanics. He was fluent in Spanish, an expert horseman and a marvel at physical comedy, but rarely had the opportunity to display his talent.

He grew up in Salinas with his boyhood friend John Steinbeck and rode an old swayback horse to school every day, which later served as inspiration for Steinbeck’s “The Red Pony.” Their friendship reached far into adulthood, and Max introduced Steinbeck to Gwen Conger, who would become Steinbeck’s second wife.

He began his career in a Harry Langdon comedy when his brothers Jack and Blake invited him on the set and began to pile on makeup and fake hair, eyebrows and a beard to give him the old man look. From that moment he was an actor. He became a regular in Universal’s “The Collegian” series (1926) and had small parts in “The First Auto” (1927) and “The Thrill Seekers (1927). A year later the popular actor and director Harry Sweet sought him out for a role in Sweet’s experimental film “Rhythms of a Great City in Minor” (1928) that made early use of jump cuts.

When talkies arrived, Fox cast him in a series of Spanish-language films for the studio’s Foreign Department. Billed as Max Barón, he appeared in “Cupido Chauffeur,” “Entre Platos y Notas,” “El Valiente” and “El Ultimo de los Vargas,” all in 1930.

The 1930s were a day actor’s dream with dozens of small roles available as studios churned out hundreds of films monthly. Mascot serials were particularly lucrative for the young actor, as he was cast in 1934 in “The Lost Jungle” and Tom Mix’s “The Miracle Rider” (1935). For the “Mexican Spitfire” series, director Leslie Goodwins recruited Max to monitor Lupe Velez’s ad-libbing in Spanish because she was prone to use profanity.

Max loved the western genre, but directors insisted that he was best cast as gangsters and policemen. He appealed to his agent in 1938 to emphasize his horse-riding skills. He won a number of western film speaking parts during this period, but he could never shake his brawny image of a tough guy.

Preston Sturges, however, appreciated Max’s flair for physical comedy, casting him in a delightful non-speaking part in “The Palm Beach Story” (1942). Over the opening credits Wagner plays the best man to groom Joel McCrea as they race willy-nilly from home to the altar for McCrea’s wedding. It’s a wonderful piece of slapstick by both actors. Max became a stock player for most of Sturges’ films throughout the 1940s.

In limited screen appearances, he still managed some nice turns as the bouncer throwing James Stewart out in the snow in “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946), Jake, a cynical detective in “The Strange Loves of Martha Ivers” (1946) and Durko, the “ugly” henchman in “The Racket” (1951). His most notable role was sixth billing as Sgt. Rinaldi in “Invaders from Mars” (1953), in which he attempts to impress his general by scouting the Martians’ hideout only be captured and turned into a drone.

While Max received screen time in high profile films like “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962), “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” (1962) and “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), it was television that gave him steady work for the rest of his career. Although generally a background player in “Gunsmoke,” he made at least 70 appearances as a townsman or barfly. “Bonanza” also offered steady work along with “The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.” A rare speaking part came with the 1959 “The Rifleman” episode of “Blood Brother.” He played John Stoddard, who had a falling out with Marshal Micah Torrance, played by Paul Fix.

Max never achieved the solid body of work as a character actor like many of his contemporaries who started with him in silent films, but he was a participant many of the motion pictures considered icons of Hollywood’s most creative period.

SOURCES:

Jack Wagner Internet Movie Database biography

Blake Wagner Internet Movie Database biography

Robert H. Wagner Internet Movie Database biography

Max Wagner Internet Movie Database biography

PERIODICALS and DOCUMENTS:

Oxnard Daily-Courier, Dec. 9, 1915

Jackson Wagner draft registration, June 5, 1917

Blakeley Allan Wagner draft registration, June 5, 1917

Jackson Wagner enlistment record, 1919

Exhibitors Herald, Oct. 30, 1920

Los Angeles Evening Herald, 1921

Exhibitors Trade Review, July 29, 1922

Motion Picture News, Aug. 9, 1924

Exhibitors Trade Review, Aug. 9, 1924

Photoplay Magazine, October 1924

Universal Weekly, Vol. 24, No. 26, 1926

Motion Picture News, March 1927

American Cinematographer, September 1927

Variety, December 1927

Motion Picture News, June 1928

Exhibitors Herald & Moving Picture World, Nov. 24, 1928

Filmograph, June 15, 1929

International Photographer, May 1930

International Photographer, June 1930

The Film Daily, June 25, 1930

Exhibitors Trade Review, July 5, 1930

International Photographer, November 1932

Modern Mechanix, April 1933

Hollywood Reporter, June 2, 1933

International Photographer, November 1933

Hollywood Citizen-News, Oct. 12, 1934

Detroit News, May 8, 1940

New York News Syndicate, July 4, 1943

Los Angeles Daily News, Aug. 4, 1943

Daily Variety, April 11, 1945

Modern Screen, July 1945

The Screen Writer, May 1946

British Air Ministry, Crash Investigation, Jan. 6, 1947

The Screen Writer, November 1947

Modern Screen, Vol. 47, June 1953

Los Angeles Mirror-News, Aug. 11, 1955

Film Bulletin, Sept. 5, 1955

Robert Aldrich letter to Paul Kohner, Dec. 20, 1956

Montreal Gazette, Oct. 15, 1957

Maxwell Sergins Wagner birth certificate